Contents of a Presentation via Zoom to Kimberley Fire Institute (KFI)

Delivered by Chris Henggeler, Kachana Pastoral Company, 19 May 2020

(Hyperlinks have been added to the text, allowing more detailed exploration of ideas that, some readers may find provocative.)

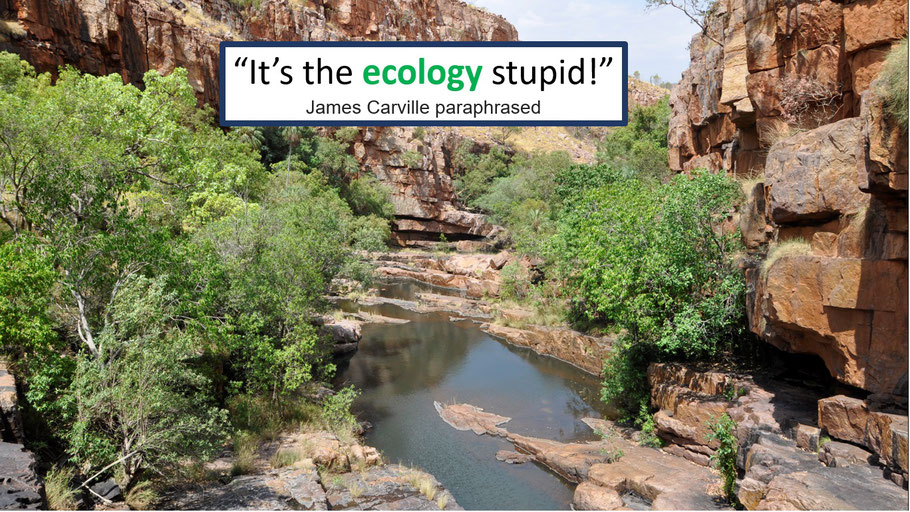

The words “ecology” and “economy” focus on the ancient Greek word “oikos”.

“Oikos” means “household”.

One is knowledge about the household, the other about the rules that govern the household.

In a basic household:

- things go in to make it up

- things happen

- things leave as waste, or wasted

Asking questions, allows us to listen to and to learn about what goes on.

Not only people have messages.

Country is full of information.

In landscapes that are largely devoid of humans, I encourage people to use their own five senses to try and interpret what nature is telling us.

Two questions might help us explore more closely what is going on, as we walk or ride through Kimberley Landscapes:

First Question: What is the surface like?

When water is splashed on, does the surface respond more like paper or more like a tea-towel, or even a sponge?

How well does water penetrate the surface?

The next time you get the chance, test the surface for water-penetration and run-off.

Use a water-bottle and conduct your own experiments.

Second Question: What might be the consistency of the ground below the surface?

Ground that we cannot see unless we dig into it?

Would it look like cottage cheese or more like cheddar?

If you were a little plant, into which one of these would you wish to send your roots to look for air, water and food?

People come to the Kimberley for different reasons:

- Scenery

- Sunshine

- Wide open spaces

- Starry nights

- Birth

- Employment

- Opportunity

- Adventure

- …

Often it is a combination, but there is a vital ingredient that allows us to stay and live in this region; that is water.

Water is critical for biology to function.

Life on Earth cannot survive if the planet becomes like Mars.

Only the right biology can buffer the physical forces that would otherwise kill us.

Water is key.

So, what is the story of our water?

Pictures like this only tell a fraction of that story.

The part relating to some of the things we do with water.

But this is water that has already dropped out of the sky.

We need to be aware of how water is being managed within the bigger Kimberley house-hold

- What happens before it drops out of the sky?

- How does it enter the house-hold?

- Then the things we do with it … as alluded to in the pictures above

- Also: How does water leave the house-hold?

I work closely with a friend in South Africa.

Each year they too have one or more mini-droughts.

Some years are worse than others. In 2018 Cape Town nearly ran out of water.

Cape Town's Day Zero water shortage fear spreads in South Africa (qz.com)

Cape Town's 2020 population is now estimated at 4,617,560.

In 1950, the population of Cape Town was 618,051

Sydney's 2020 population is now estimated at 4,925,987.

In 1950, the population of Sydney was 1,689,935.

We are talking about 4.6 million people here; a population only slightly smaller than that of Sydney...

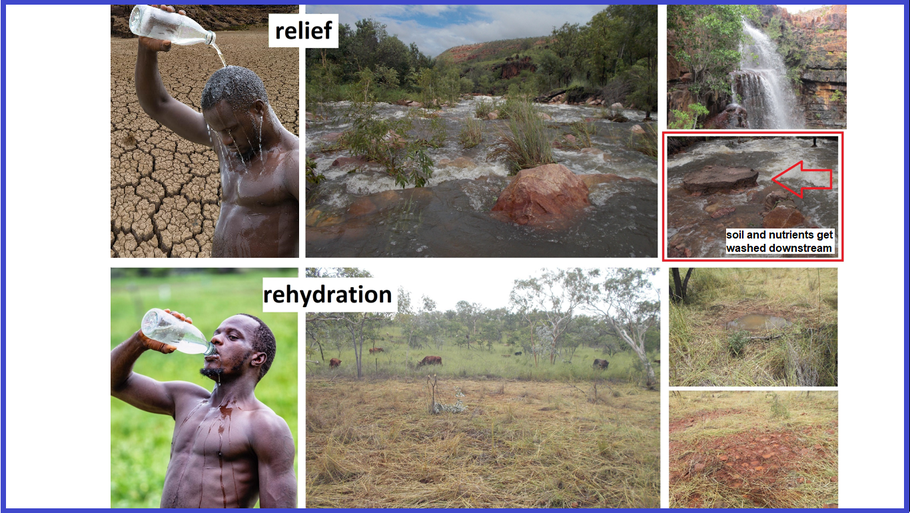

If eventually it does rain, what is the response?

Different continents, but the same processes …

Relief often comes with momentary abundance and wastage.

To rehydrate, water needs to percolate through a body or the soil

How are things closer to home?

The Dunham Pilot Dam, Dec 2019

If we go out in October and take a close look at the edges of a dam that is drying out (in this case the Dunham Pilot Dam), we can see for ourselves whether the trends favour “cloth and cottage cheese” or “paper and cheddar”.

Remember: “It’s about the ecology!” Learning how a particular household functions.

We’d need to follow the energy as well as follow the water … (today we follow the water)

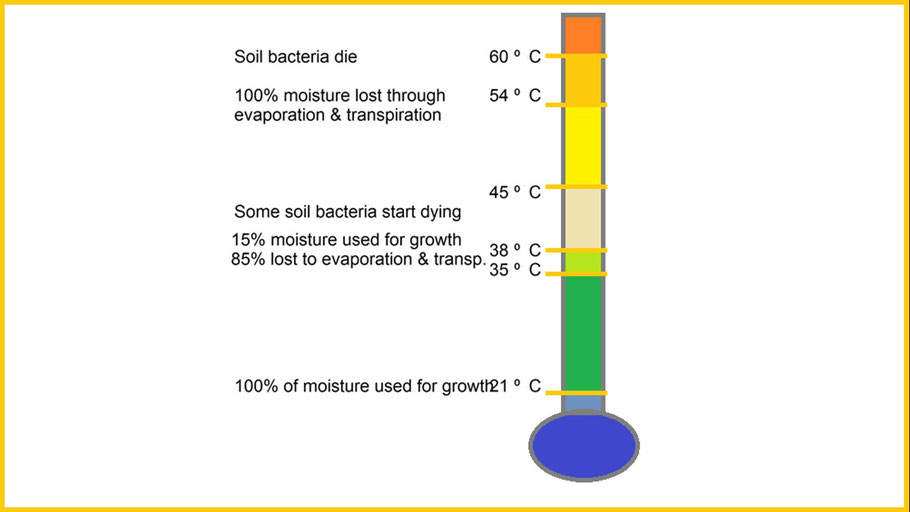

Whilst doing so, let us bear in mind that heat and radiation both kill.

- Ground cover protects against heat and radiation

- Bare ground loses moisture

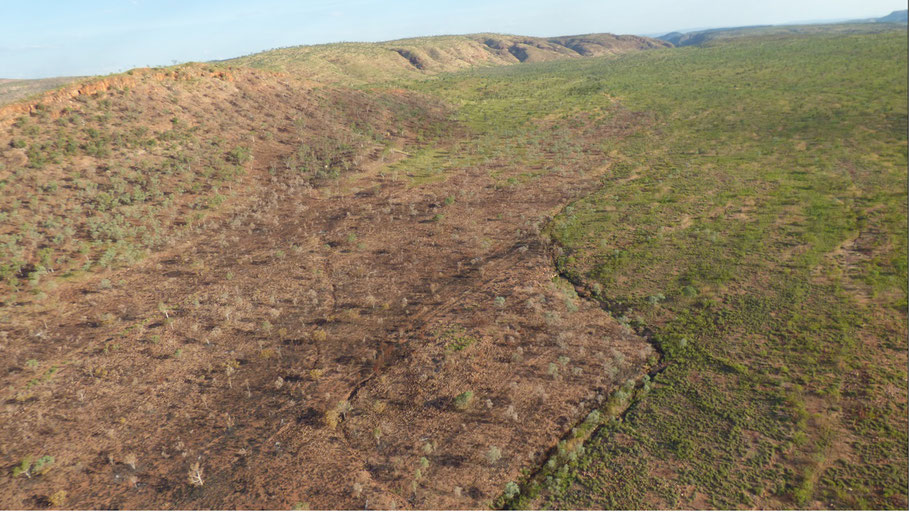

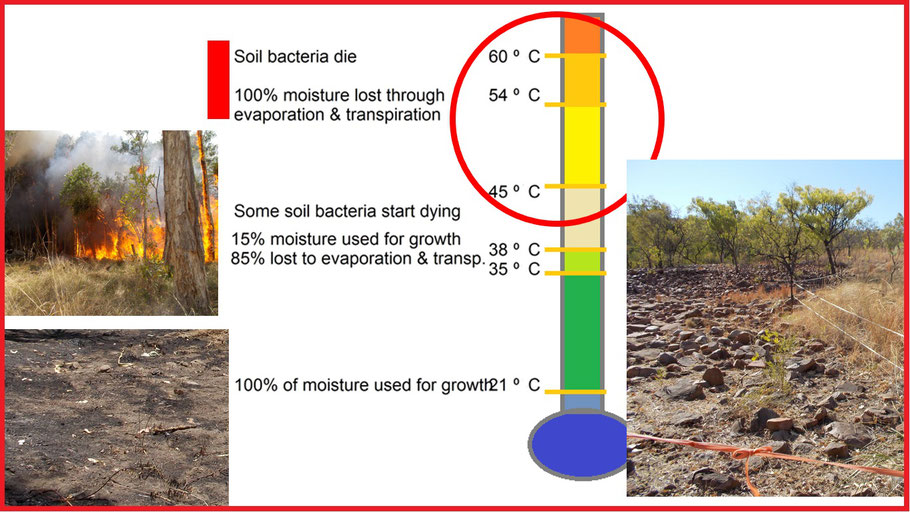

Fire and high animal-impact are both powerful tools

Both use and release sunlight energy

Like bulldozers and chainsaws both can serve as valuable tools.

Like bulldozers and chainsaws, when misused, both can contribute to soils being exposed on a massive scale.

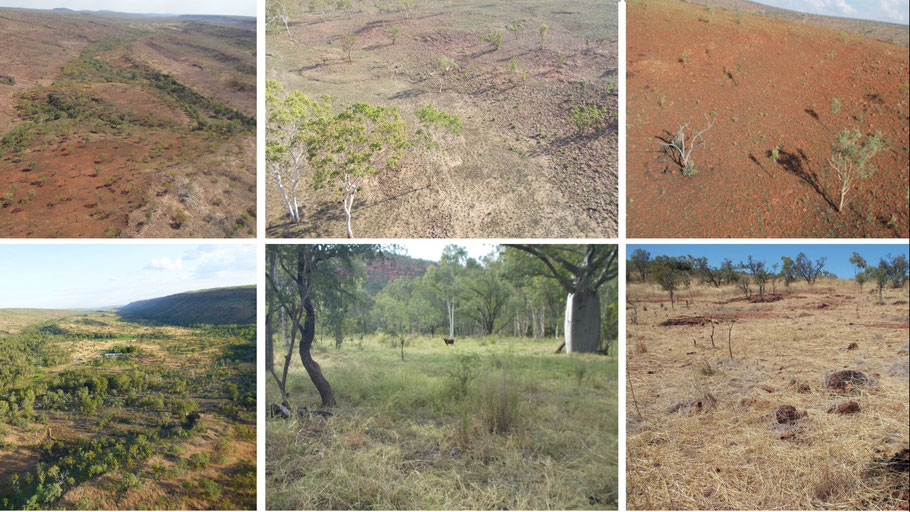

On the left we have soil exposed by fire

On the right we have ground exposed by frequent high animal impact.

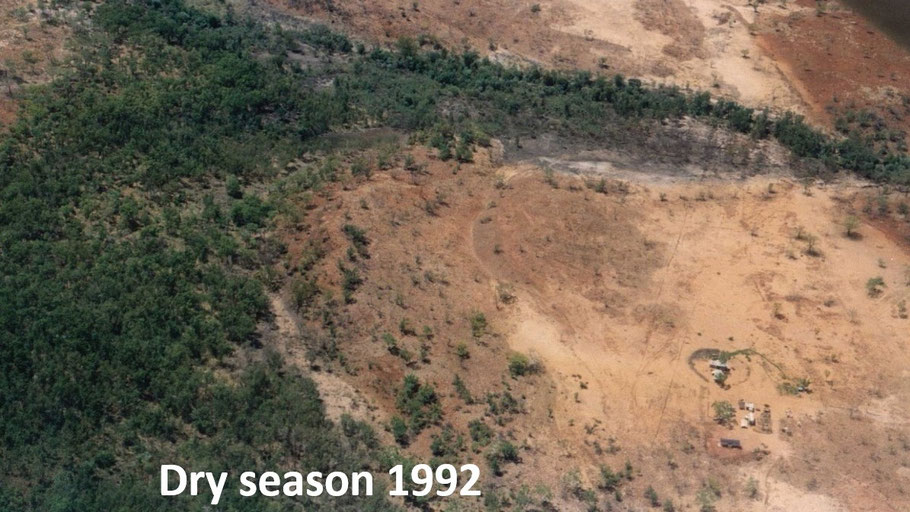

In 1991 we set up camp on Kachana.

What information did the land give us?

The household is squandering the basic ingredients: Sunshine, Water and Land

- Sunshine heating up and dehydrating the land…

- Water runs off and takes soil and nutrients with it or it evaporates off bare ground

- Minerals & nutrients being leached out and washed away…. or blown away.

In areas that could on occasion support fire, nutrients were being exhausted into the atmosphere…

- Biodiversity was being lost …

The commercial value of feral stock would not have covered the costs of getting them off the place.

Desertifying land means life in the soils is dying.

Desertification is a costly process.

If allowed to progress, it will eventually kill the Australian economy as it has already killed small businesses and rural communities in the past.

Floods wash away soil, cut roads, weaken bridges and wreck infrastructure.

e.g. After the 2011 floods, the bill to the tax-payer to rebuild the township of Warmun exceeded $ 200’000’000.00.

Droughts regularly affect Australian communities and late 2019 some towns were trucking in water.

Fires in Australia regularly make global headlines.

Costs that impact people’s lives, livelihoods and communities, end up being reflected in national economies.

Our beautiful region is not being spared from the law of the harvest.

Much of what we grow in the Kimberley each year goes up in smoke within three years.

Water is being lost and not stored.

In unmanaged catchments soils are dying and eroding.

Full costs include not only escalating band-aid measures, but also the loss of potential livelihoods and industries.

We also witness a loss of social capital as long-term residents leave the area.

After living in these landscapes since 1985, I conclude that the horse has already bolted.

The good news is:

We may have a fighting chance to reign him in: rebuild soils according to nature’s template.

With an average of over 600mm rainfall, the Kimberley has no legitimate excuse for desertification.

We’d need to use the same processes that provided the original natural wealth that humans have been tapping into for millennia.

Functions that were originally performed by our lost megafauna need to be reinstated.

Regenerative pastoral practices can do this by putting to use Australia’s new megafauna.

In fact, it may be our only viable option if we wish to sustain the sort of life-styles modern Australians are accustomed to.

With planned and managed animal-impact we cover the ground with mulch and evenly distributed fertilizer.

Changing the landscape surfaces from “paper” to “tea-towels and sponges” allows water to stay around for longer.

Creating the conditions to allow soil-structure to change from “cheddar” to “cottage cheese” allows water to penetrate deeper into the soil-profile and to extend growing-seasons.

Growing plants feed the soil-microbes that build and maintain soil-integrity.

For dam-building, roadwork and erosion-control we often choose powerful big yellow machines to do a job, but that does not mean that they need to remain on site.

Similarly, when we use animals as a tool for a specific job, this does not necessarily mean that they need to remain in a landscape once the job has been done.

This means there is no legitimate reason why some animals could not also be used as tools in national parks and other areas beyond farms and stations.

After all, to manage fuel loads, respond to wildfire, and to deal with the damage caused by fire, drought or flood, we regularly use people, fire-trucks, graders, aircraft, etc..

None of these were here 300 years ago!

So why not work with willing, healthy animals that run on renewable energy?

At the end of the day if we can agree on what it is that we wish to see in our Landscapes, laws of nature will determine whether or not this is possible.

“Landscape goals” actually determine how landscapes need to function.

Local contexts then determine what viable options are available to achieve such outcomes.

It would then make sense to choose the most appropriate tools and operators for the job.

So often, we justify the use of finite sources of energy in the from fossil-fuels to achieve a planned outcome.

I stress here that the use of fire in the face of deteriorating soils is much the same as burning up finite fuel-reserves.

Do we opt for ever increasing intensive care until we run out of energy, or do we rebuild a vibrant and resilient Kimberley household?

I wish the KFI group well in building the sort of social capital that is needed to turn things around.

With open communication and the building of trust, I believe that much is possible.

Chris Henggeler, Kachana Station