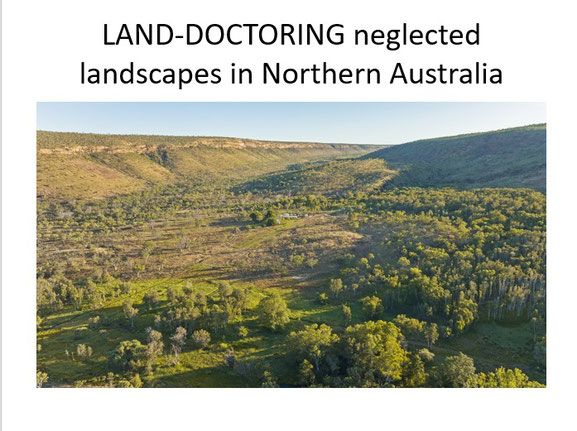

LAND-DOCTORING neglected landscapes in Northern Australia

Slides and commentary from a power-point presentation given by Chris at the GROUNDED conference

Tasmania, 04 December 2024 - Chris Henggeler, Kachana Pastoral Company

1.

2.

Over ten years ago Martin Royds made the following observation:

Alex Podolinski, Bill Mollison, Arden Anderson, Allan Savory, Elaine Ingham, Peter Andrews,

Fred Provenza, Walter Jehne, … … we just about know them all personally.

What are we waiting for?

We need to get to work! NOT KEEP WAITING for more gurus to appear!

It is a conference like this that tells me that Martin was not alone in his thinking.

We all stand on the shoulders of giants and it is great to be able to compare notes.

I thank Matthew for inviting me here today, to share some of my journey.

3.

As a young man, Dad was given the job to carve a ranch out of a portion of wild Africa.

This was in the early fifties on the slopes of Mt Kenya.

That is where Dad picked up first-hand on multi-species interactions and the role of herds in a landscape.

Dad ended up in Rhodesia with his own little mixed farm, only much of the game there was already locally extinct and the land not very productive.

4.

I grew up on the watershed between the Zambesi and Sabi Rivers in southern Africa.

Water was limited and soil-erosion was a reality.

Dad was using cattle at high densities as a land-management tool, for the mulching, even distribution of fertilizer and the pruning of vegetation.

As a passionate hunter, he proved to be an effective custodian of local game.

5.

This included leopard, hyenas, jackals, wild pigs, porcupine, kudu, sable, water-buck, duiker and steinbok. Then there were a whole lot of other mainly smaller and nocturnal species.

In the seventies, Dad began reintroducing locally extinct species like impala, zebra and eland.

He was winning land-care trophies but not making money with cattle.

This dilemma got solved by subsidizing his land-care efforts with photographic safaris.

6.

After the Rhodesian civil war, we lost our farm.

7.

Having seen the writing on the wall, the family had already relocated to Switzerland, which is where I finished high-school.

8.

After the African bush I got to enjoy and respect the wild side of Switzerland: the mountains.

As in the bush: If you do not play by nature’s rules, it is easy to die.

9.

I have farming blood in me from both sides of the family, and I was looking for a piece of land to regrow my roots.

10.

Europe was too crowded for me so I kept going, and ended up in Australia.

Australia in 1979 was a free country.

Friendly people, wide open spaces, a land of opportunity.

You got something for me to do?

What’s your name?

Chris.

I’ll give you a chance to prove yourself.

No paperwork. No nanny-state.

As a young buck, I’d spend around eight months of the year up North working on stations.

During the summer months I used to head down South doing odd jobs on farms.

What I saw I liked, but I was under no illusions.

Already in my first year in Australia, I came to the conclusion that Australia was unforgiving.

If you had all your assets in just one rural enterprise, no matter how good you were, if it did not rain for five years, you’d most likely have a problem.

1983, with some partners and borrowed money, we started investing in real-estate and increasing rental values.

It was that real-estate back-stop that later permitted me to tackle the learning-curve that came with Kachana.

11.

1985 I first came across Kachana.

It was not exactly what we had been looking for, but it ticked all my boxes and then some.

12.

There was sunshine, water and limited soil, … enough to run a small herd.

Close enough and far enough from town.

Obvious tourist potential would allow for diversification, and reduction of risk.

1989 we got our Lease.

Creating access was the next challenge.

I continue to nurture this old-fashioned notion that farm-families remain integral building-blocks in any healthy economy.

Plan “A” was to have at least three committed families.

For three bachelors, as we were back then, that was easy enough to say!

Today on Kachana, sadly, we remain at least three families short of target.

13. Christmas 1991 we set up camp as a family… … and Kachana became home!

14. The Henggeler family 1997

15.

By the time we had moved out, we had also realized that not all was well in these beautiful rugged landscapes.

The very areas that had attracted us were fast disappearing.

1992, before we commenced management, we got the Department in to conduct a “stock-take”.

16.

With the blessing of the Departments at the time, we began experimenting by applying an African skin-graft to an aboriginal wound.

Planting material was supplied by staff at the research station.

Ideas were shared and we were learning together.

In order to hold onto what soil was left, we employed New Australian deep-rooted pasture species and Dad’s “high-density low-duration” herd management techniques.

By 1995 we had regained perennial stream-flow.

We were consistently seeing very encouraging results, but could they be sustained over time?

The land was trying to tell me something.

Something was missing. Something was not quite right!

Late 1996 I got to drive through South Africa. I’d only read about the game and antelope migrations. Relatively speaking, all that I saw, was a biological vacuum.

Then I visited our old farm in what had now become Zimbabwe. Here at least, I had 40 years of personal perspective.

Dad then invited Jacqueline and I to join him in Kenya for a fortnight.

As we enjoyed the landscapes, Dad would describe what had been there 50 years earlier.

This was not what we were observing now!

Early 1997 we got back home to Kachana.

17.

This photo was taken 20. November 2024

This is what we have now, after having rationed out approximately 900 SDHs in the last 12 months, and on top of feeding a whole lot of marsupials.

But let’s first go back to 1997.

18.

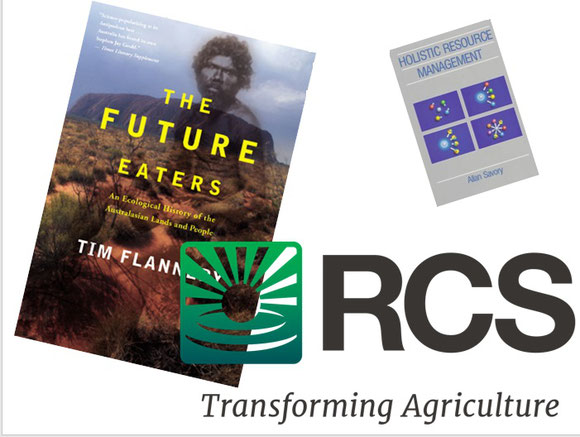

1997 was a key year in a number of ways.

Apart from a new Land Act in WA which put us on the wrong side of a supposedly politically correct fence, I was given Tim Flannery’s book to read.

WOW! So, a very long time ago, Australia did have large herbivores!

As a blow-in from Africa, that was huge news to me!

Then Terry McCosker introduced me to the concepts of “brittleness” and “succession” and the teachings of Allan Savory.

Now, at last, I could better begin to understand what the land had been trying to tell me:

Not unlike a cholera patient, who fails to digest nutrients or hold onto fluids, the land was dehydrating and literally wasting away.

As with an auto-immune disease where a body works against itself, sunshine and rain, instead of producing abundance were destroying life, and human-lit fires and absent grazing regimes were compounding the issue.

I had already suspected that the land was starving, dehydrating and burning up with a fever for months at a time, but now I realized that in order for these landscapes to heal, we needed more mouths and more hoofs, not less!

The gardeners of the savannah were missing.

Mouths and hoofs strategically massaging the land.

I needed to go back to school.

For the first time in my life, I did so willingly.

My study of ecosystem-function continues to this day.

For any other students, but especially for would-be students of eco-system function, I will

with broad brush-strokes quickly run through ‘ecology 101’

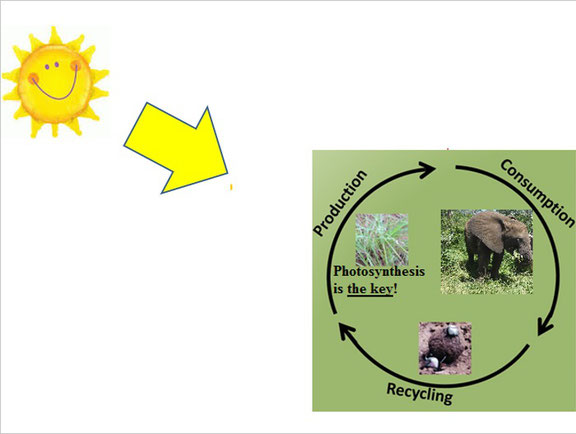

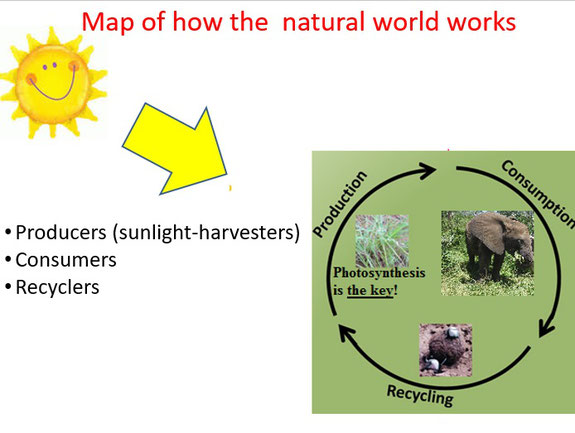

19. This is actually a “map”:

MAP 1/5

20.

In functional savannah landscapes we find three teams at work:

- Producers or sunlight-harvesters (as we like to call them)

- Consumers

- Recyclers

These teams do not compete.

They actually play for each other… using sunlight energy to up-cycle water, carbon and nutrients.

I’ve got the elephant in there because it is the largest land-based herbivore left on the planet.

According to scientists nearly all of Australia’s large herbivores disappeared soon after humans arrived on this continent.

21.

Modern humans have become the apex-predator and alpha-consumer.

There is nothing wrong with consumption…. provided we play by Nature’s rules…

… and production and up-cycling continue.

22.

Sunshine may be the fuel that runs life on earth…

And by all accounts, there is no shortage of carbon in the air…

23.

However, Water in the right quantity, at the right time, is fast becoming a limiting factor…

… at times even in the Kimberley.

24.

World-wide we are finding that more grass is a very doable step that leads to more water.

25.

Unmanaged fuel-loads tend to be ticking time-bombs

Hence, in the absence of sufficient self-regulating herbivores, we need to manage what grows.

26.

We’d be naïf to think we can ever have everything under control.

27.

Where possible, we use our animals to manage fuel-loads…

Only we do not have enough herbivores to process what grows each season.

Over the last thirty years we have had to contend with a major wild-fire every three years, on average.

In practical terms this means - if we do not wish to lose 100% of our litter every three years, we need to strategically burn about one third of what grows each season.

Fire is a tool. Fire will always be with us.

In a key-note presentation, Chris Henggeler outlines remote catchment challenges to delegates at a “FIRE FORUM” hosted by DFES (Broome 2017) The original presentation was delivered in 25 minutes, followed by 35 minutes of questions and discussion. In order to encourage a lively exchange of ideas, no recordings took place at the time. July 2021 Danny Carter joined Chris on Kachana and filmed this version of the presentation. “Custodianship is core business.”

For a PFD version of the slides and text please CLICK HERE https://www.kachana.com/Ka%20DFES-201...

28.

Regenerative pastoral practices are based on an understanding that healthy savanna systems run on sunshine, and that sufficient herbivores are there to keep vegetation and soils healthy.

This is the sort of result that we are after when we first treat an area: applying and spreading nature’s sunscreen

When I first treat country, I will use animal densities of up to 1200 head per hectare. (That does not mean that I have that many animals; we just bunch them up to achieve that level of density.)

For greater detail watch Chris presenting at the Landscape Restoration workshop at Yarrie Station, Pilbara WA

29.

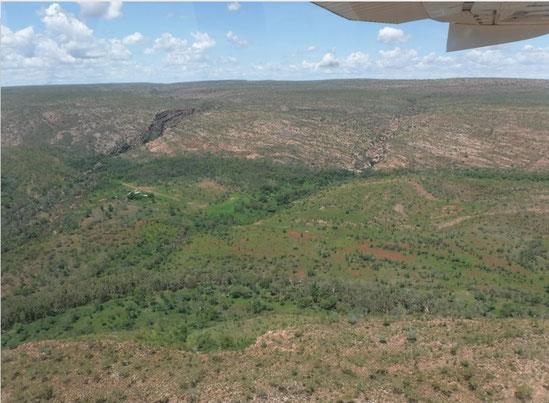

I have spent over 35 years riding and walking in, and flying over this particular bit of country

In many of our Kimberley catchments, we can see the results of a three to five-year fire-cycle …

Bear in mind this is not country that supports Australia’s beef exports.

This is country largely abandoned by industry players. And that, for obvious reasons:

there is no buck to be made unless you mine it.

Yet, for centuries this country was inhabited and productive.

Now such areas are largely out of sight, out of mind, and dehydrating.

It has become the sort of country that increasingly grows wildfire, droughts and floods.

30. We zoom in, to a case-study: Marshall Creek Sponge

31. It is within walking distance of where I’m based.

32. It used to be a wetland-sponge

33.

- There has never been any mechanical disturbance in the area.

- For over 30 years, we have maintained 100% stock-control.

- The last fire was in 2005.

34. … we are only just beginning to halt the deterioration…

35.

If we get fire in here now … even a “cool” burn…

water is going to run off faster… and take loose stuff with it…

36.

… soil-erosion and loss of biodiversity will again accelerate…

37.

Season after season, bit by bit, we are losing sponge after sponge in many areas of the Kimberley, and possibly also in other regions of Northern Australia.

38.

The last four photos were taken here:

39.

This is would have been the extent of the wetland-sponge 100 years ago… perhaps even only seventy…

40.

About this much of the sponge has been lost since 1991…

I’m not sure that we can be growing organic horizons and building soil if we lay bare the ground every three years.

41.

I suspect that even if we were to introduce this level of complexity…

… we could not heal our sub-catchments or rebuild our sponges… … if fire were our only tool…

The deterioration would continue.

The results would be the same… only blurred and slowed down because some species would hang in there for longer.

Next door, and in the region, much country is now being managed by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC).

They’ve only been at it for twenty odd years. However, they would be beginning to accumulate some interesting data, and we hope to compare notes.

Human use of fire is known to shape landscapes.

Fire can be a “blunt tool” and used randomly, but if used appropriately and in the right context, it can be a versatile “precision tool”.

On occasion Kachana is invited to weigh in at local discussions.

2020.05.19 - Contents of a Presentation via Zoom to Kimberley Fire Institute

2022.11.03 - KPC Contribution to the 'East Kimberley Community Fire Forum'

42.

Soil-loss takes place not only in sponges…

In terms of volume, soil remains North Australia’s greatest export.

43.

I wish to emphasise the first point:

In high rainfall areas desertification is easily masked by seasonal changes.

Each year, news headlines support the notion that by the time the symptoms of desertifying watersheds impact communities, no amount of remedial work downstream, will reverse any dysfunction up-stream.

44.

We see here, the Dunham River joining the Ord.

The only reason that the Ord is still cleaner is, because there are two dams upstream of here.

These slow down flood-water in exchange for most of its sediment-load.

45. Now we are 120 km upstream. This is where the water begins to get its colour.

We are in an area where we have spent most of the last 40 years replacing herbivores with fire.

I reiterate I am not talking about country that is under sound pastoral management.

I am talking about country where conventional pastoralism is not, or no longer feasible.

46. Flooding begins even higher up in the catchment.

Notice how floodwaters have flattened the grass.

47. The actual watershed is now a skeleton of a landscape with no soil left.

It sheds clean water. - Now we go to the other side of the same water-shed.

48. This is upper Cockatoo Creek on Kachana.

The same skeleton of a landscape, the same rainfall and also clean water because the sponges are long gone, there is no soil left.

49. This is lower Cockatoo Creek after rain on the range. (30. January 2021)

Notice how clear the water is.

We use vegetation to hold soil in place and to filter water.

50. Walter Jehne calls them “mobile biodigesters”.

We influence herbivores, so they can exercise their natural function, which is to keep vegetation healthy.

51. When we set up camp (1991), the land around us was crying for help.

Today lower Cockatoo Creek has reliable perennial stream-flow.

“The water is now there because of the grass.

The grass is now there because of the way we influence the behaviour of large herbivores.

Nibblers, in our case a range of marsupials, then follow to do their bit.

But there is a catch! And that has to do with the greater context.

52. We ZOOM out….

- Watersheds in the region continue to desertify.

- This pattern is not unique

-

For the price of an airline ticket, we can take a trip into the future!

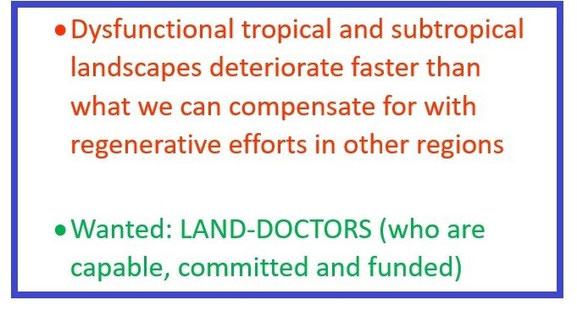

53.

Different context, even a different continent, and more people, but the patterns match:

- bare watersheds & catchments dehydrate and erode

- low fuel-zones remove the fire-danger

- we take advantage of nutrients being washed into valleys

- wildfire becomes less of an issue

- however, droughts & floods increase

- then again, band-aid measures boost GDP and create photo-opportunities

- eventually production areas begin to dehydrate

- people run out of water and communities are in conflict

For an idea of the social fall-out watch the world news.

45.

At the time, decisions seem easy to justify.

But actions have consequences.

55.

And when complex, dynamic, living systems are involved actions often bring about

unintended consequences.

Dehydration is a leveller like few others.

Olympic athlete, concert pianist or obese chain-smoker, take away their fluids for 3 days,

and their individual performances will end up about the same.

So it is at the landscape level.

Even the best regeneratively managed farm, cannot be sustained over time within a dehydrating and desertifying landscape.

56. The best regenerative practices downstream cannot reverse ecological dysfunction upstream.

My assessment is that in many regions in Northern Australia, the horse has already bolted.

Yet I believe we stand a sporting chance of reigning him in.

For that we need a new generation of land doctors capable and willing to work in country that is known to be inhospitable.

Basic skill-sets that such land-doctors will require already exist.

They have been tested and are being embraced by leading industry players.

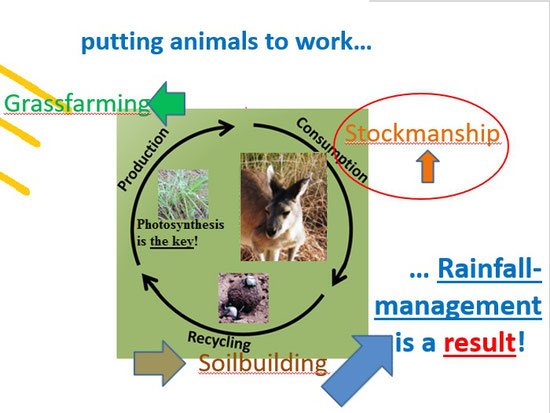

57.

Skills required, are listed on the right… Let me unpack this slide

58.

As Stockmen we influence ultimately all herbivore behaviour

The key is Grassfarming: – Functional herds grow healthy vegetation - Christine Jones talks about liquid-carbon pathways.

A rapid increase in photosynthesis can draw down carbon and begin to put it back to where it will work for everybody.

The area of maximum impact is Soilbuilding: - Healthy plants feed the organisms that build and maintain productive soil. – Elaine Ingham explains very well what should be happening in the world below our feet.

We rebuild and fill up carbon-accounts in and on our soils.

In a cattle enterprise, an increase in the kilos of beef/ hectare is the easiest way to measure success.

WATER-SECURITY and biodiversity are also useful indicators.

59.

Stockmanship, Grassfarming and Soilbuilding reward us with what I call ‘Rainfallmanagement’.

Rainfallmanagement is a result!

It all begins with sound pastoral practices.

We end up hanging on to a little more water for a little longer each season…

Rainfallmanagement allows us to rehydrate soils, and to replenish ground water and aquifers.

60.

NOTE: Rainfallmanagement is a result of blending Stockmanship and Grassfarming, with Soilbuilding!

“Climate” is how we personally get to experience the interaction of these four simple, but complex processes.

“Climatebuilding” is what needs to happen.

It will be achieved by rebuilding the buffering capacity of biology, in the face of physical forces that are already aligning to determine our extinction as a species.

Some years ago, Walter Jehne reminded us that, as she has done before, Nature will again stabilise climate.

The critical question he left for us to answer, was:

Will she do it now and with our help, or after, and without us?

I wonder: Is she perhaps beginning to do so despite us?

After all we do all live within a self-regulating system…

Rainfallmanagement, understood as a process, is a result of how we manage or influence the first three processes.

Rainfallmanagement will also determine our viability…. …as regions… … as communities … … as businesses.

What may be easy to forget, is that climate too, is a result.

Again: Climate is how we experience the interaction of these four processes.

Climate-stability is what we aim to achieve as we rebuild nature’s biological processes and buffers.

We begin by rebuilding microclimate and then strategically growing that out into catchments and across regions.

61. Armed with these pastoral skill-sets we can now go about restoring ecological basket-cases…

62. … within workable time-frames

63. But let’s get back to the elephant in the room

Remember, wild-fire, droughts and floods grow mostly beyond managed production areas.

And often, in desertifying upper-catchments that remain out of sight and out of mind.

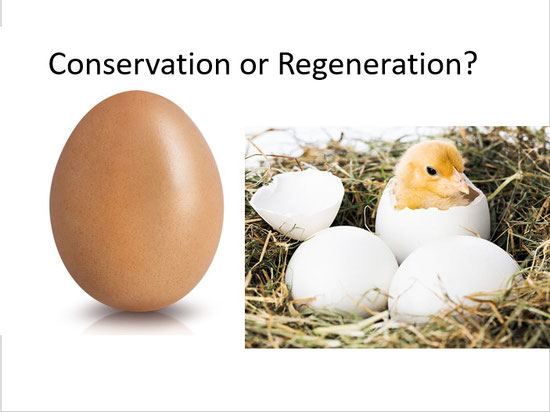

64. Intact egg-shells versus chicks?

“Change isn’t the exception to the rule, It’s the only rule.” Fred Provenza

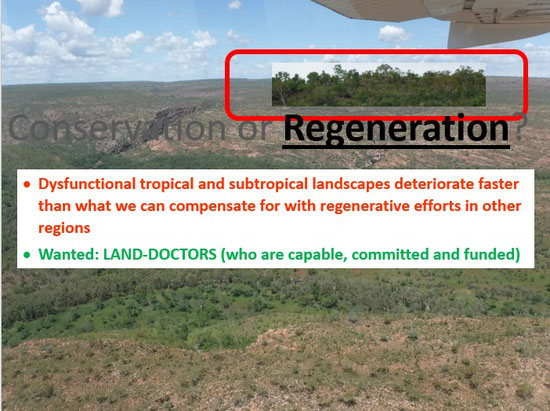

65.

From what I have witnessed in my life-time, it is now too late to still be asking this question.

When the Salmond River self-destructed in 2001, nobody paid attention.

In 2011, Nobody took notice of the Chamberlain story.

One might have thought that the over $200,000,000 repair bill for the Warmun floods, would have led to questions being asked. – Not so, at least nothing has happened to address their root-cause.

Then in 2023, immediately to our Southwest, the Fitzroy River presented the tax-payer with a further 500,000,000 dollars in costs. ("Record flooding in Kimberley causes widespread destruction ...")

A surprising lack of scientific curiosity persists.

People in power feel able to deal with these supposed effects of “climate-change” from the confines of their caged work-places some 3000 kilometres away.

The reality that surrounds my work-place, dictates that healing and regeneration remain bottom-up processes.

Even if our big-city cousins wake up and regulators were to stop penalising innovation, work that needs to be done must be driven by local enthusiasm, and with community backing.

66.

Rebuilding the lost Cockatoo Creek Sponge is one of my retirement projects.

After numerous set-backs, we plan to begin with this project in 2025.

Chris Henggeler, Kachana, Kimberley WA

May we prove to be worthy heirs of privileges that came at a high cost.

Backdrop slide for question-time:

As pastoralists we can offer solutions that are in line with how nature works.

Solutions that are: family friendly , community friendly, low tech / high skill

Solutions that promise: new knowledge, new skills, new jobs, new industries & new wealth!

This gives me hope, for us and our children and grandchildren.

With appropriate incentives, Land-Doctoring could begin at an industry scale!

However, treating players in the industry like serfs, wage-slaves or tax-slaves, will not cut it.

I suspect that it will take more than a jackaroo’s wage to incentivise able-bodied young people to commit to Land-Doctoring as a career-path or vocation.

Brian Marshall asks: How do you tell an earthworm or a dung-beetle what to do?

The answer is: You do not. You create the conditions for them to perform.

Now, there is a vacuum for political leadership to step into!

It remains my firm belief that if we were to trim the ecological sails appropriately, in landscapes around us, nature would fill them faster than most of us could imagine.

GROUNDED Australia - Farming Better plans to upload videos of filmed presentations.

Links

- GROUNDED Australia - Farming Better

- Speakers - GROUNDED Australia

- Recorded presentation: Land Doctoring in Australia's North (46 minute video, including questions)

- Links to all videos taken at the GROUNDED CONFERENCE

- kachana pastoral company uncensored - Kachana Station